16th Century: Origins & Early Development

Technological Advances

A Fabric That Barely Exists

Lace has always been a paradox: a fabric defined as much by its absence as its presence. It is a fabric made of air shaped by thread, yet for centuries it has carried the weight of wealth, power, and desire. From the stiff ruffs of Elizabethan portraits to the whisper-thin veils of haute couture, lace has traced the outlines of how we see beauty, gender, and craftsmanship.

Today, you might find lace on a Dior runway, a thrifted blouse, or a handmade doily in your grandmother’s drawer. But its story begins in an age when every thread was precious and every pattern carried a secret code of status.

The Birth of Lace: A European Obsession

The word “lace” comes from the Latin laqueum, meaning “snare” or “noose,” which is a fitting origin for a fashion phenomenon that would soon ensnare the European elite in the late 16th century. There is no exact date for the invention of lace, but its foundations likely emerged from humble, utilitarian roots in farming and fishing communities, where simple knotted patterns formed mesh fabrics used for nets and bags. This was a cost-efficient technique that required less material than traditional weaving on a loom.

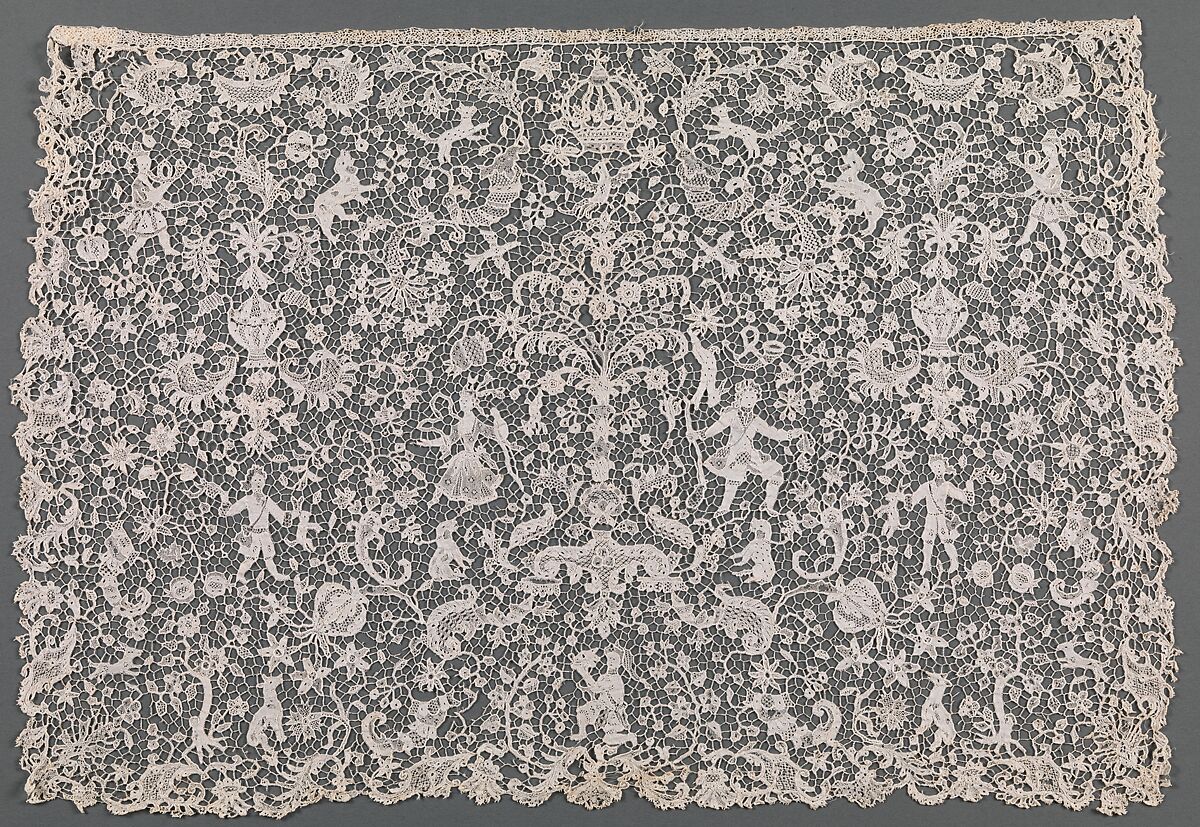

Handmade laces developed in the early 16th century in the Venice and Milan areas of current Italy and in the Flanders (modern-day Belgium) area in northern Europe.

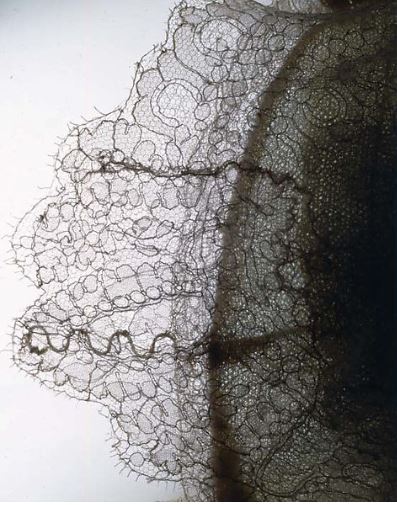

Two styles emerged: needle lace, created by making looped or knotted variations on the buttonhole stitch with a threaded needle on top of a pattern, and bobbin lace, created by twisting, crossing, or plaiting multiple threads wound on bobbins, spindles on which thread is bound. While both were incredibly time-consuming to make, as bobbin lace became more complicated in design, it became a cheaper and faster alternative to needle lace.

Despite the advancement in lace-making technology, the craft was extremely expensive to make, as a square centimeter could take 5 hours to produce. Furthermore, high-value materials, such as fine linen threads, silk threads imported from China, and even gold and silver threads, were materials often used in lace. Naturally, lace became the symbol of Renaissance luxury, its dense floral reliefs adorning the robes of popes and princes. Across the Channel, Queen Elizabeth I’s starched lace collars fanned out like suns — both armor and aura. Lace became an early form of wearable power, as political as it was decorative.

17th Century: Expansion & Symbolism

Technological Advances

By the 17th century, lace had become Europe’s soft gold. Monarchs built entire economies around it. France’s Louis XIV established state-sponsored lace workshops to keep money from leaving the country. In England, laws restricted who could wear imported lace. Smugglers hid contraband lace under cloaks and in coffins.

Cultural Impact

A Neckwear of Male Identity and Power

In the 17th century, lace played a prominent role in elite men’s attire, particularly in neckwear (collars, falling bands) and cuffs. The adoption and display of lace signified status, refinement, and sartorial power.

_-_Louvre_Museum.jpeg)

One of the dominant collar forms was the falling band: a broad, flat, white collar often trimmed with lace, which replaced the earlier stiff ruff and became widespread after the first half of the century.

Lace collars were frequently matched by lace cuffs—the cuffs of the shirt or doublet being decorated with similar openwork lace. These paired sets of collar and cuffs were a customary ensemble for men of fashion.

Furthermore, starting in the mid-17th century, men’s shirts sometimes featured a jabot, a decorative lace ruffle or insert at the front opening, hanging downward and often visible beneath a waistcoat or overcoat. The jabot evolved in this period as a visible lace embellishment of male dress.

17th Century: Women’s Lace & Stylistic Innovation

Stylistic Developments

A Canvas for Stylistic Innovation

In women’s dress, lace appeared more extensively and in more varied contexts than in men’s attire. It functioned not just as border trim, but as structural ornament: collars, ruffs, rebatos, cuffs, caps, coifs, and decorative inserts.

Elite women at court and in wealthy circles incorporated lace into their collars, ruffs, and coifs. For women, lace was a sign not only of wealth but of refinement, beauty, modesty, and adherence to courtly elegance. Because lace frames the face and neckline, it carried visual weight in portraiture as a halo-like decorative aura.

Women’s lace often employed reticella (geometric needle lace) and punto in aria (freestanding needle lace off the ground). Reticella was especially popular in early 17th century collar and cuff work, favored for its lacy grid structure and classical geometry.

.jpeg)

As fashion progressed, more ornate Venetian needle lace (Point de Venise) was also used in women’s collars and decorative dress panels, especially among aristocratic circles. The most renowned was Gros Point, distinguished by its bold, three-dimensional Baroque patterns that seemed almost carved from ivory. Lighter variations soon followed, including Rose Point, with raised but more open motifs, and the delicate Point de Neige, where clusters of tiny loops created a snow-like texture. A flatter, simpler style known as Point Plat was also made but never achieved the same acclaim.

In France, Point de France began to emerge as a desirable domestic alternative to imported Venetian lace. The late-17th-century Point de France lace used motifs such as suns, fleurs-de-lis, and crowns, echoing Louis XIV’s iconography.

Because women’s clothing allowed wider surfaces and decoration, lace became a canvas for evolving artistic techniques, so lace in women’s garments tended to push stylistic innovation more than in men’s relatively constrained neckwear.

18th Century: Rococo, Refinement, and the Art of Sheerness

Technological Advances

Early Rococo Innovations

The early 18th century marked a transition from the dense, sculptural needle lace of the previous era to increasingly delicate, airy patterns with open mesh grounds. French needle laces such as Alençon and Argentan, and Flemish bobbin laces like Binche and Valenciennes, became synonymous with refined Rococo aesthetics. These innovations paralleled the era’s fascination with lightness and elaborate ornamentation, with lace serving as both surface decoration and a subtle symbol of status.

Late-century Chantilly Craze

By the latter half of the century, the fashion world witnessed a surge in the popularity of Chantilly lace—a fine black bobbin lace that originated in France. Its delicate patterns and versatility made it a favorite for ruffles, cravats, corset trims, and hair accessories. Concurrently, Mechlin lace from Flanders gained prestige for its clear ground and bold floral designs, further broadening the stylistic palette available to designers and wearers alike.

Through the 18th century, lace fashions shifted from the dense, sculptural needle lace of the 17th into more delicate, airy patterns and open mesh grounds. By this time, French needle laces (e.g. Alençon, Argentan) and Flemish bobbin laces (e.g. Binche, Valenciennes, Mechlin) became dominant in the high-end lace market.

- 1620: Lace introduced in France

- 1700: Bobbin lace gains popularity

- 1800: Machine lace invented

The lace style known as Chantilly lace (a fine black bobbin lace) became fashionable in France in the mid-18th century. Mechlin lace (Flemish bobbin lace) was highly prized, especially for its use in ruffles, cravats, corset trims, and hair accessories (coiffures de nuit).

Another variation, Blonde lace (a silk bobbin lace made in France), grew in popularity during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The natural color of the silk thread gave it its name; the bold floral motifs made it well suited to the gathered trimmings of period garments.

19th Century: Industrialization & Democratization

Technological Advances

Industrialization and Democratization in the Early to Mid 19th CenturyTechnological Advances The 19th century saw major technological breakthroughs with the invention of the bobbinet machine in 1809 by John Heathcoat, which enabled the mass production of net grounds necessary for lace. This innovation, along with subsequent improvements in lace machinery, allowed for the creation of complex patterns and made machine-made lace widely accessible. These advances dramatically reduced the labor required compared to hand-making techniques, democratizing lace and opening new avenues for design and ornamentation. Cultural Significance Lace continued to symbolize refinement, femininity, and social status throughout the 19th century, but its meaning evolved. With broader access, lace appeared not only in elite wardrobes but also as decorative trimming in middle-class fashion. The material gained new associations with purity and romance, particularly through events like Queen Victoria's 1840 wedding, which established lace as an essential element in bridal wear and ceremonial dress across Western culture. Economic Impact The industrialization of lace production transformed its economic landscape. Once a luxury reserved for the elite, lace became a significant commercial product, supporting entire manufacturing sectors in regions such as Nottingham and Calais. The lower cost of machine lace fueled a boom in demand, creating new jobs and export opportunities. However, this shift also undermined traditional hand-lace industries, leading to the decline of artisanal workshops in favor of factory production.

Late in the 18th century, early machine lace experiments began, but it was 1809 when John Heathcoat invented a machine capable of producing a stable “net” ground (that would not unravel when cut), which made more complex lace feasible by machine.

Over the course of the 19th century, lace machinery improved rapidly. By mid-century, many types of hand lace had machine-made equivalents. Lace became more widely accessible to middle and upper-middle classes. Whereas lace had once been reserved for aristocracy, by Victorian era it appeared as decorative trimming on everyday dresses.

Because machine lace could be produced at scale, ornamentation expanded: dresses featured lace panels, lace overlays, and lace dresses themselves rather than just trimming. The interplay between volume, texture, and layering became important in Victorian aesthetics.

Yet, lace became strongly associated with bridal wear and purity, particularly after Queen Victoria’s wedding in 1840, when she wore a lace veil and dress (Honiton lace). This event cemented lace’s status as a symbol of virtue and romance in Western bridal culture.

20th Century: Intimacy, Revival & Subcultural Rebellion

Early 20th Century

Early 20th Century: Lace as Intimate and Structural Fabric

In the early decades of the 20th century, as fashion silhouettes became simpler and less adorned, lace moved inward. Rather than being purely a decorative overlay, it became integral to lingerie, undergarments, and structural surfaces.

Designers such as Coco Chanel and Madeleine Vionnet embraced lace not just as border trim but as textural and structural elements, integrating it into bias cuts, draped panels, and soft lines. The incorporation of synthetic fibers, such as rayon, further expanded possibilities – lighter weights and new drape effects allowed lace to function as part of the garment’s architecture rather than only as decoration.

Mid–Late 20th Century

Mid–Late 20th Century: Revival, Couture Reassertion & Subcultural Rebellion

With the postwar fashion revival, lace reemerged as a marker of luxury and couture craftsmanship. Christian Dior’s “New Look” (1947) reinvigorated romantic femininity, bringing lace trims, lace bodices, gloves, and veils back into high fashion. Houses like Givenchy and Balenciaga further integrated lace into gowns and bridal couture, reasserting its status as a couture material.

At the same time, lace became a vehicle for subversion. From the 1970s onward, punk, goth, and new romantic subcultures appropriated lace in contrast, layering black lace over leather, using shredded lace, or exaggerating lace jabots and cuffs in a camp or androgynous style. Icons like Prince and Boy George revived historic lace accessories (jabots, ruffles) in defiant, iconic fashion.

Designers also began to explore technological hybridizations: laser-cut lace motifs, lace appliqués on synthetics, digital embroidery, and experimental mesh/lace composites. These techniques blurred the lines between lace as craft and lace as a digitally mediated, structural element.

21st Century: Heritage, Identity, and Material Dialogue

2025 Trends

21st Century: Heritage, Identity, and Material Dialogue

The global lace market was valued at $1.2 billion in 2024 (McKinsey, 2024).

In the contemporary fashion landscape, lace no longer commands singular meaning. Instead, it lives in the tensions between tradition and innovation, craft and technology, transparency and identity.

Many regional lace traditions (e.g. Burano, Alençon, Pag) have been revived and supported by heritage institutions, UNESCO recognition, and craft schools. At the same time, designers are pushing lace into new territory: laser-cut lace, 3D-printed lace structures, and computer-generated lace motifs now appear regularly in both couture and ready-to-wear.

In 2024, UNESCO listed Venetian lace as an intangible cultural heritage, underscoring the ongoing global recognition and preservation of lace-making traditions.

Today, lace stands for heritage, irony, gender play, and material poetry more than explicit status. It features heavily in discourse about slow fashion, craft revival, and material storytelling. In fashion now, the interplay between void and structure, opacity and transparency often serves as a conceptual prompt, with lace used to express ideas about vulnerability, skin, layering, and identity.

.jpeg)

Key Takeaways & Modern Relevance

- Lace’s evolution mirrors shifts in technology, social status, and gender expression throughout fashion history.

- Technological advances—from handwork to machine lace to digital fabrication—expanded accessibility and creative potential.

- In the 21st century, lace bridges heritage craft and high-tech innovation, symbolizing both tradition and experimentation.

- For fashion teams and designers (like those using Make the Dot), lace’s journey underscores the importance of material research, collaborative creativity, and the enduring power of textile storytelling in design.

.png)